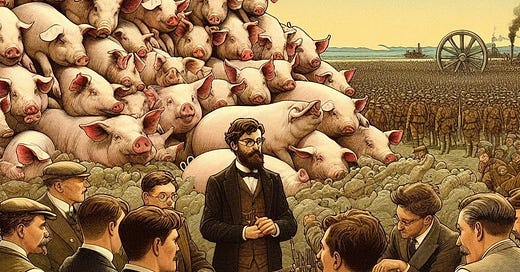

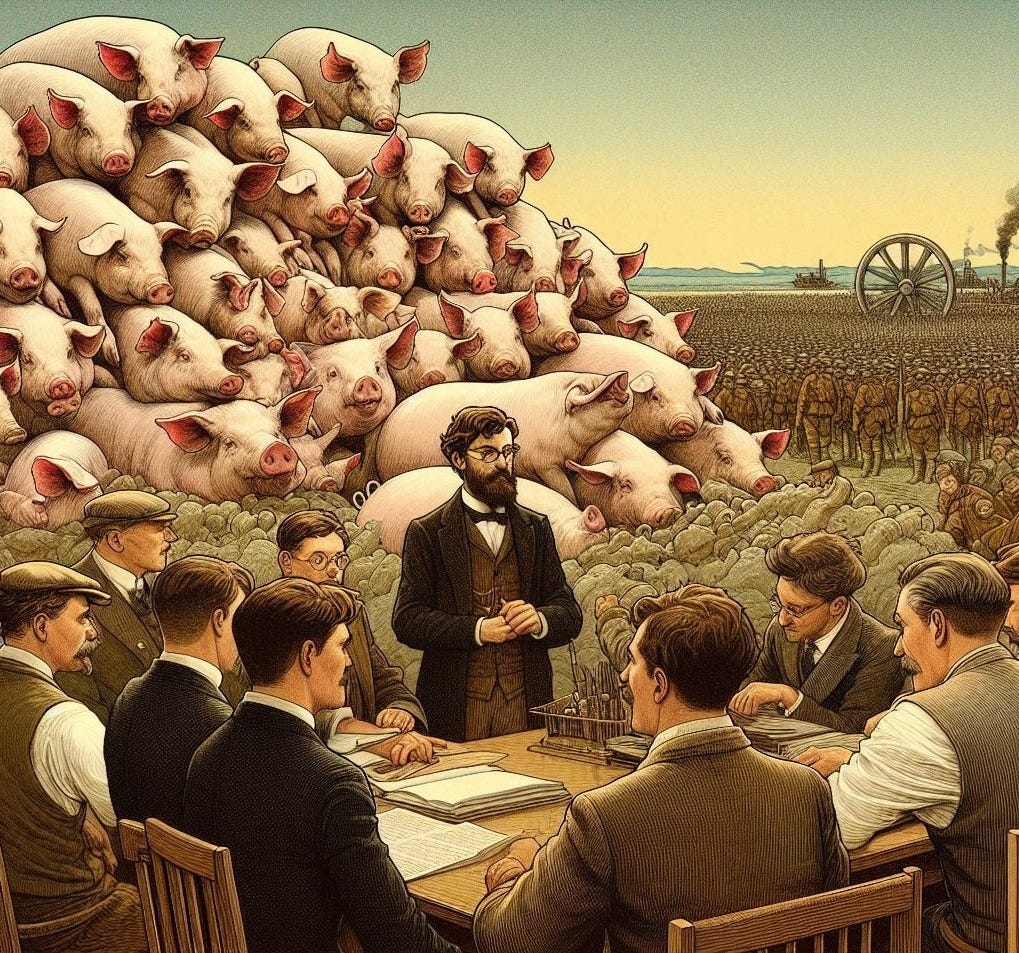

The Pretence of Knowledge: Why Professors Ordered the Slaughter of Five Million Pigs

How a World War I Crisis Reflects Hayek’s Warnings Against the Illusion of Control in Economics

“Even a fool may be wise after the event.” – Homer, The Iliad.

In the history of economic policymaking, Germany’s decision to slaughter millions of pigs during the First World War stands out as a particularly striking misstep. Initially seen as a crucial measure to prevent hunger, it highlights the risks associated with what the Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich August von Hayek called “the pretence of knowledge” - the overconfidence that leads policymakers to believe they can manage complex economies with precision.

The Blockade and the Food Crisis of 1915

Before World War I, German military authorities considered the risks of an economic and food blockade by Britian but took no substantial action. At the start of the war, the public was assured of sufficient food supplies, despite Germany producing only 80% of its food and relying on imports for the rest. However, the British naval blockade and the interruption of trade with Russia soon made shortages obvious. By winter 1914/15, it was clear that action was needed to secure food supplies. Furthermore, a survey in early 1915 revealed a significant shortage of grain and feed potatoes for the country’s 25 million pigs. Historians now question the accuracy of these reports, suspecting that the fear of government seizures may have led to widespread under-reporting, distorting these statistics.

The Drastic Decision to Slaughter Five Million Pigs

Seeking solutions, the government consulted academic experts who recommended the slaughter of five million pigs. The plan seemed logical: by reducing the pig population, more supplies would be available for bread and other staples. However, the implementation soon revealed significant flaws.

Unintended Consequences and Economic Fallout

The immediate oversupply of pork caused market prices to collapse. Efforts to preserve the meat were only temporarily successful because the cans were made of inferior tinplate, as the higher quality metal being diverted to arms production. As a result, by autumn of 1915 much of the meat stored in spring had spoiled, driving prices to unprecedented heights. Despite efforts at rationing and price intervention, the market was soon dominated by black market dealings and price gouging. High meat prices incentivized farmers to feed livestock with grain and potatoes meant for human consumption.

By 1916, the reduction of the pig population caused also a shortage of pig manure, crucial for fertilizing crops, especially as nitrate imports were largely blocked. As a result, crop yields plummeted from pre-war levels. The resulting scarcity and lack of dietary variety, coupled with shortages of heating materials, clothing, and hygiene products, increased susceptibility to diseases and lead to an estimated 800000 civilian deaths1.

Lessons from History

The mass slaughter of pigs illustrates the unintended consequences of a seemingly rational and straightforward policy. This event reflects Hayek’s warnings against the illusion of control in economics. Friedrich von Hayek’s argues in his lecture “The Pretence of Knowledge” that the failure to make economic policy more successful is largely due to the fact that social sciences, like economics, grapple with structures of essential complexity. Hayek defines “essential complexity” as situations in which the variables involved are too numerous and interconnected to be easily understood or accurately predicted.

The Interconnected Factors of the mass slaughter of pigs

During World War I, policymakers faced essential complexity in the mass slaughter of pigs. Agricultural, economic, social and wartime factors were deeply intertwined, creating a web of dependencies and feedback loops that were not fully understood. This complexity was evident in the numerous factors and the dependencies at play: the impact of trade blockades on supply chains, farmers underreporting supplies due to fear of government seizures, inadequate materials for meat preservation, the emergence of black markets, and the livestock-crop interdependence i.e., the vital role of pigs in producing manure for fertilizing crops. Missing a factor in one area had cascading effects on others.

Hayek’s Perspective on Imperfect Knowledge

Hayek cautions that in domains dominated by essential complexity, it is impossible to obtain the complete knowledge needed to make mastery of the event possible. He pointed out that we can only identify some, but not all, of the circumstances, factors and interdependencies that determine an outcome; hence we cannot accurately predict the outcome. Hayek prefers “true but imperfect knowledge, even if it leaves much indetermined and unpredictable, to a pretence of exact knowledge that is likely to be false”. Policymakers, Hayek suggested, should use the knowledge they can achieve not to shape the results like a craftsman shapes his handiwork, but to cultivate the right environment, much like a gardener tends to his plants.

Can the Study of Historical Events Make Us More Overconfident?

When reflecting on historical events, it often seems easier to identify the relevant factors and interdependencies. However, historians highlight what we now know were important. We now know the exact sequence of events rather than the multiple possible pathways and associated uncertainties that people faced at the time, making the event look simpler, more linear, and more predictable than it was. This phenomenon is known as hindsight bias - the common tendency for people to perceive past events as having been more predictable than they were. An important consequence of hindsight bias is that it can make us more susceptible to overconfidence. This, in turn, can lead to the beliefs about one’s ability to make sound judgments in general and increase the risk of overconfident actions (policies) in the future. This underscores the importance of being mindful of the limits of our knowledge and the inherent difficulty of making predictions within structures of essential complexity.

Conclusion

The mass slaughter of pigs in Germany during the First World War illustrates that even well-intentioned policies can lead to disastrous outcomes. It underlines Hayek’s skepticism about the ability of economists to predict and control economies with precision and highlights the importance of humility and caution when attempting to manage complex systems, recognizing the limits of our knowledge.